M. Krasikov

Ukrainian student subculture as mirrored in

epigraphy

The fact that the studentship is a special

unique subculture, that is Уa sovereign integrated formation

within the reining culture which is distinctive by its own scale

of values, its customs and normsФ

1, as well as by its slang and folklore, has long been

obvious not only to researchers (cultural† studies and political

studies researchers, ethnographers, folklorists, psychologists,

philosophers, linguists, sociologists) but also for those who

were once lucky to belong to this corporate community.

†††††††† For the past 15 years in the

republics of the former Soviet Union (especially in Russia) there

has been a growing interest in the modern student subculture on

the part of folklorists and ethnographers which is stipulated by

the democratization of public life and the attention to

non-formal cultural formations, youth formations in particular in

all their diversity

2. It is quite logical that we find a

Student traditions chapter in the

Modern City Folklore collected works

Ц the first and, alas, the last up to now fundamental work

on the subject

3. The majority of the works on the modern studentship

describes omens and superstitions, specific rituals ( before

examinations, transitory etc), jokes, tales (fables) and other

narratives, sometimes there are also humoristic decodings of

abbreviated words, Уkey wordsФ and dictionaries of slang.

†††††††† We are going to try and consider

student subculture through the alembic of epigraphy (graffiti) Ц

writings and drawings on desks, walls, various interior objects,

billboards etc.

†††††††† Our work is based on a considerable

collection, completed in 1990-2005 by the author in the National

Technical University УKharkiv Polytechnic InstituteФ (NTU

УKhPIФ), Kharkiv National Karazin University (KhNU), Kharkiv

State Academy of Culture (KhSAC) and Kyiv National Shevchenko

University (KNU). The results of 1999, 2001 and 2005 students

polling will also be considered.

†††††††† Why is epigraphy so eternally

attractive for students?

†††††††† Unlike other folklore genres,

sometimes put into written form for the sake of memorization

(mnemonic purpose), (in songs collections, demobbed albums etc),

for teenagers fixation of some texts on everything that comes to

hand is only occasionally aimed to facilitate memorization, but

basically

it is the elemental manifestation of free self-expression and

its purpose is communicative. We should take into account

that Уthe doers of graffiti are not always their authors but much

more often their УtranslatorsФ and Уare representatives of a

certain behavioral stereotypeФ (namely, group stereotype).

However, there is much of the† personality in the act, as the

choice of a Уlyric heroФ always takes place. In fact, it stands

for choosing the self-image, Уwhich the writer creates, which he

identifies himself with Ц consciously or subconsciously Ц

firstly, by the very fact of writing and, secondly, by the

content and the form of the inscriptionФ

4.

†††††††† Out of the first-year students of

three departments of KhPI (168 people, 59 female and 109 male),

questioned by us in 2001, only 13.5% (22 people, 12 boys and 10

girls) never write or draw on desks. 7.1% (12 people, 11 boys and

1 girl) mark desks with graffiti

regularly. As it has been expected, the majority Ц 78.2%

(134 people) do it sometimes or occasionally (86 boys and 48

girls, 78.8% and 81.3% respectively). In March, 2005, we

questioned first-year students of three departments and

fifth-year students of one department of KhPI and got similar

results.

†††††††† In 2005 the respondents were asked

the question: УWhy do you think people write on desks and walls?Ф

The most typical answers were: УBecause they convey their ideas

that come up suddenly and [a person Ц M.K.] is overwhelmed by

certain emotionsФ, Уto be humorousФ, Уbecause you wouldnТt write

a thing like that in a newspaperФ, Уout of idlenessФ,

Уself-expression + boredomУ, Уfools have nothing else to doФ, Уto

express feelings, thoughts, stupidityФ, Уthey understand nothing

[of the lecture Ц M.K.], thatТs why they are boredФ, Уthey want

to stand out (writing on the desk is poetry for themФ, Уto leave

their mark for the future generations!Ф, Уsome people would like

to put down their poems, thoughts for others to knowФ, Уto write

tests with the help of desks writings (formulas)Ф, Уnot too

brightФ, Уsometimes you just want to play a little dirty trickФ,

Уthey are inspired by their MuseФ, Уthey want all people around

them to know their ideasФ, Уa)out of boredom; b)out of excessive

sense of humor; c)in defiance of rules that prohibit doing itФ,

Уthey donТt know why they are doing it themselvesФ, Уout of lack

of communicationФ etc.

†††††††† It is characteristic that many

respondents, without long consideration, give one and the same

motivation for everybody Ц most often it is Уout of boredomФ or

Уfor the sake of self-expression!!!Ф, not less often it is the

need of communication (lack of communication) or Уa historical

markФ, Уa means to be rememberedФ. Less people (about 40%)

differentiate the motivations of different writers, for example,

as follows:

УPeople write to:

a) put down their telephone number, their name

or group-number etcФ;

b) give vent to their good or bad mood

(appropriate pictures);

c) express their attitude to some people in

the group or course, their attitude to teachers;

d) express their attitude to sports, music or

politicsФ.

We could hardly agree to the following

statement of one of the respondents: УIf lectures were more

interesting, there would be less writingФ. Boredom is not the

only and most likely not the main УimpetusФ for the graffiti. The

key motivation for Уdesk-writersФ are the unquenchable

existential significant need

to raise their voice about their values and priorities in

a most straightforward way, being unafraid to be mocked (a

characteristic reply is Уto express emotions without saying them

aloudФ) or misunderstood (this is where lies the great

psychotherapeutic force of the thing Ц such a session of

Уcreative workФ is, in fact, Уart-therapyФ and in many cases can

help as much as a visit to a psychologist). The author of

graffiti knows perfectly well (and deep down counts on the fact)

that his every saying, sign, picture left on the desk or the wall

is almost doomed to dialogical (polylogical) УcommunicationФ,

whose significant charm lies in partial or complete

anonymity. In fact, walls and desks had been

a forerunner of Internet,† that allows now to exist

comfortably under УnicksФ and to gush oneТs УPhew!Ф and УWows!Ф

towards everything in the world, frisking about thousands of

sites. (By the way, S.Y. Nekludov is absolutely right in stating

the importance and great prospects of† studying УInternet as a

quasi-folklore environmentФ

5). Nevertheless, we would take the risk to suggest

that even if the World Web creeps into every household, the

number of those who choose to scrape or draw in an old-fashioned

way on suitable surfaces in public places will not diminish, for

Уthe real realityФ has a certain advantage as compared to the

virtual reality. This advantage was very well described by one of

our respondents: УЕ It is nice to see your writings appear in

other university buildings and class-rooms. You feel like an

unknown celebrityФ.

Naturally, autographs on walls and desks are a

means of marking a new (neutral or alien) space and of

familiarizing oneself with it (Уappropriating itФ). This is the

meaning of the omnipresent УVasja was hereФ-type signs. With

students (and this is symptomatic) these are not so much

individual autographs (УmemoriesФ) as collective (group,

department) УnicksФ, which is related to

collective self-identification and collective

self-assertion:

In any class-room in any institute we can find

desks covered by columns of academic groupsТ names (sometimes in

various artistic and calligraphic manners). Often the name is

accompanied by the English У

the bestФ. Researchers rightly liken this kind of graffiti

to animals marking their territory

6. However, following the idea of A. Plutzer-Sarno, we

tend to view even such simple writings not only as Уterritorial

signs to mark the areaФ or the communicative space, but as the

means (quite subconscious on the level of reason) of magical

influence on the world, as metatexts with the regulating function

7.

†††††††† In general, student life is the key

subject of† writings and pictures, which is the evidence of†

subcultural interests prevailing over УcommonФ ones. However,

such common topics as music, sports, erotica, alcohol and (rather

less common) politics are also quite popular with students and

graffiti prove it in an eloquent way.

†It is worth mentioning that most of writings

and drawings are not of a serious nature, but humorous (most

often) or ironic. If a serious text crops up (a saying or a

lyrical outburst), it can hardly pass without a jeering

commentary. Humor is the element of freedom, its pet child, and

there is nothing strange about the fact that

the dominant feature of Ukrainian students (at least, of

those who raise their voice epigraphically from time to time) is

not simply the sense of humor but

the constant inclination towards УhumorousФ( free)

perception of any event, be it of the most serious nature Ц

ranging from inter-university to state or international levels.

Most pictures (especially erotic) are caricatures, erotic

writings play with the subject of oral sex (still viewed as

perverted by the conservative УadultФ society) and homosexual

relations, using almost exclusively Уnon-parliamentaryФ

expressions primarily for the sake of joshing. On the other hand,

it is also a manifestation of freedom, the verbal and artistic

affirmation of the personalityТs right to the non-interference in

the private life of a young person on the part of the society

(with its archaic and often bigoted moral restriction on

out-of-wedlock sex). The pronounced cynicism of certain writings,

the rudeness and vulgarity of remarks regarding the opposite sex

(often coming from girls) do not always reflect the real attitude

but are often

a play mask. In fact, graffiti are a phenomenon of

playing consciousness. In view of this, even obvious

verbal aggression, УatrociousФ invectives of xenophobic,

misanthropic or personal nature should not be treated very

seriously. This is nothing more but

a substitute to actional aggression.†

We will try to analyze in detail those

graffiti that reflect student life, its uncomplicated events,

attitudes to the learning process, to teachers and

friends.

The decodings of the self-identifying word

УstudentФ (

Rus. -

студент

) give us quite a traditional image of a

student (familiar for us from thousands of jokes), which can be

translated as У a sleepy theoretically intelligent kid naturally

disinclined to studyФ.

Or there is another version, quite popular in

Kharkiv: УA haul of money is urgently needed. Nothing to eat.

Full stopФ. Also quite a folklore image.†

The process of studying is of course the most

burning issue in the student folklore. On desks and walls we can

find parody slogans: УSleep, student! The country needs healthy

specialists!Ф (KhSAC, KhPI), УepitaphsФ: УThis is where an

atrocious assassination of Time took place!Ф and wise sayings

(reconsidered and added-to proverbs and sayings): УLearning

brings light, and you have to pay for the lightУ (KNU), maxims,

parodying religious commandments: УYou shall not snore at the

lecture for snoring you will awaken your neighborФ (KNU,

variations can be found in many Kharkiv universities), УYou shall

love you teacher for the dog is a pal for the humanФ(KNU) and

more or less tumultuous reactions to what is going on in the

class-room (silenced

cri de coeur): УWe are people though we are studentsФ,

УAll I hanker after right now is beer!Ф, УDonТt shout! I want to

sleep!Ф, УWe have been fuckedФ, УShit!!! WhatТs gonna happen to

me?!! FACK!!! I am in an asshole!!!Ф, УNot ready for the seminar!

Sod OFF!Ф, УIТll re-passФ (KNU), УthatТs it!!! I am

shocked!!!!!Ф, УHome, home, itТs time to go homeФ (KhPI) etc.

Despair is in many cases exaggerated and grotesque, as it can be

clearly observed.††

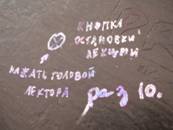

There is probably not an institute, not a

single class-room in the whole of the former Soviet Union where

you could not find a drawing of a simple device accompanied with

the corresponding instruction.

††††††††††††††† †††††††††††††††

There are also inscriptions under the

picture:

УButton for switching off the lecturer. Press

with the forehead and waitФ. УButton for catapulting the lecturer

into space. If it does not work, try by handФ, УButton for

switching off the lecturer. Press with the lecturerТs forehead

ten timesФ.

Of course, almost every class-room can УboastФ

of a caricature pictures of УfavoriteФ teachers, often

accompanied with offensive inscriptions, for example, УS. is a

bitchФ.

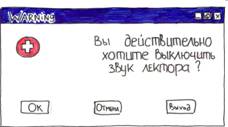

Sometimes the following picture is drawn on

the vertical surface turned to the class:

On the walls and desks there are enough

writings addressed to the pedagogical staff and few of them are

positive.

Most often they read as follows: УLook here,

Maz, we gonna meet in a dark alley. Well-wisher and Co.Ф

There are many unaddressed writings of a

generalizing nature:

УFuck you prepod Ц son of a bitchФ; УA good

teacher is a dead teacherФ etc.

It even makes one think about the rightness of

the maxim inscribed on one of the desks in the graffiti-famous

class-room 214EC in KhPI: ФIf studentsТ prayers were answered,

there would not be a single teacher left aliveФ.

Naturally, there are a lot of poetic works

dedicated to the hardships of studentsТ life.

There is a remarkable example of playing with

the Soviet symbols in a picture expressing the authorТs attitude

to learning:

Sometimes the drawing of the crossed hammer

and sickle goes without verbal commentaries, but only some

first-year students on seeing the picture on the desk can treat

it as a sign of studentsТ commitment to communistic ideals and of

their nostalgia after USSR and not as a call to skip

lectures.

In any big cityТs student community there are

teasing verses directed at students of different professions,

humoristic explanations of the universitiesТ abbreviated names

and jokes and anecdotes on the subject.

As we do not have the opportunity (on account

of the volume limitations) to dwell upon either the purely

erotic, musical, sport, political topics of student graffiti or

the latrine (toilet) УclassicsФ and additions to written message,

we would like to say that in this sphere we can observe the same

situation as was described by K.E. Shumov on the basis of his

Perm materials. In many points our research backs up the

observations and conclusions made by the authors of the

City Graffiti article. However, not all of them.

†Namely, we believe it is too early (at least,

for Kharkiv) to conclude, as it has been done by our Russian

colleagues, that Уlately the society has ceased to be actively

discuss and disapproved of writing on walls in public places and

to treat it as reprehensive and marking its doerТs behavior as

anti- or asocialФ

8. In 2001 18.8%† of the students questioned stated

their negative attitude to writing on desks or walls, while in

2005 it was 16.4%. There is a certain reduction but it is not

significant enough.

When asked if they had heard remarks from

their teachers about those who wrote or drew on the desks, 63.2%

answered positively in 2001, and 46.4% answered positively in

2005. Although we can observe a clear downward tendency, 46.4%

does not seem a small figure.

So, it is too early to speak about tolerance

to graffiti on the part of the older generation (pedagogues, in

particular, and they are a community apart).

We cannot agree either with the final

conclusion of the authors of

City Graffiti: УModern graffiti are losing their

significance as a sign of protest or alternative to the official

culture and actualizing their dialogical material they are

extending to the maximum their Уsphere of influenceФ in the

communicative system of the modern cityЕ At the same timeЕ the

difference between intragraffiti and extragraffiti level of

communication is practically disappearingЕФ

9

Without dwelling upon all the types of modern

graffiti and speaking only about student graffiti we cannot say

that they are losing their oppositionist function. On the

contrary, epigraphy is often

the only accessible for the student form of expressing their

disagreement (moreover, quite a safe one) with the suggested

Уconditions of existenceФ, complicated or boring lectures, highly

demanding teachers, disciplinary reprisals of the deanТs office

etc.† By the way, according to the sociological research carried

out in KhPI in 2000-2004 (the same 225 students of all

departments were questioned once a year) every third student says

that learning materials are put into a learner-unfriendly form,

while 44.7% of first-year students, 46.5% of second-year students

and 41.6% of third-year students complain about the saturated

schedule of mandatory tasks. How can oppositionist texts fail to

appear on desks, if 51.8% of students in their second year are

already disappointed with their choice of profession or

university, among third-year students the figure is 61.2%, among

forth-year students it is 61.1%! With the time passing, the

interest in the learning process is, as we can see,

falling.††

УBeing alternative to the official cultureФ

remains essential for the modern Ukrainian authors of graffiti.

The powerful parody current in the studentsТ creative work is

directly connected to the purposeful УdebasingФ of official

literature, pronouncedly drastic vulgarization and profaning of†

Уthose lyrical thingsФ.

This is clearly the obstinate rejection of

Уready-madeФ texts, truths and life schemes which are to be taken

for granted. This is a form of cultural and generational

alienation from the adult world with its tedious institutional

means of upholding the УmoralityФ.

The predominantly negative evaluation by

teenagers of the

Уprocess of the compulsory obtaining of informationФ is,

of course, connected with the well-known age-related negativism,

the attitude to antonymic perception of the УparentФ discourse,

but at the same time it is also an evidence of the real faults in

the existing educational system.

As to the extension of the Уsphere of

influenceФ of graffiti, we must say that a great number of them

sill remains functional only within their УmotherФ subcultures.

Out of a certain locus (a class-room in this case) many of them

lose their meaning. Many of the above-mentioned graffiti are not

known at all beyond the social group of students, even among

teachers who linked to students. That is why the openness and

readiness to participate in a dialogue (a polylogue) of student

graffiti authors do not mean that the replies received will be

got from УoutsideФ (it is difficult to imagine a teacher writing

an answer to his student offender. So, we are speaking here about

intragraffiti communication locked within its community, though

not so hermetically as some other youth subcultures.

To sum up, it should be said that it is

graffiti Ц a parafolklore means of keeping and transmitting

folklore information Ц that give us the most adequate, unadorned

vision of the studentship.† Of course, the image we get is that

of a brutally charming trickster, of a unpleasant (lazy, sly,

cynic, unlearned) and not intelligent person (even not in the

future). Is it the true picture of an average modern student and

why is it what we see in the mirror of folklore? May the mirror

be distorting?

One of the answers is tradition. In the

base mass culture the main features of the student† have

been carelessness, merry-making and alcohol-drinking since the

times of

the vagants.

Nonetheless, we should say that

alcohol-drinking is of a declarative and conditional nature (as

well as drug-taking and erotomania are mainly virtual) and the

verbalization of desires, fulfilling the compensatory function

can often successfully substitute their realization in the

real. Even real-life student binges are often akin to

rituals. Demonstrative deviancy (not so considerable in its

percentage Ц according to K.E. Shumov only 22% of all writings in

the Perm university touch upon untraditional sexual relationship

10 and we observe practically the same situation) is a

sure sign of† the necessity of self-affirmation: you cannot stand

out if you are the same as the others?

Foreign words in inscriptions are also a mark

of distinction and initiation, but this Уesoteric qualityФ

contains an oppositional element not only towards the profane,

but towards the official

Ukrainian culture.

Swear words which are not a common language of

communication for many students, as our research shows, are still

used in some on-desk writings Ц and this is also a mark of

belonging to a subculture, where this stratum of vocabulary is as

used (to a certain degree) as jargonisms of different origin and

specific student slang. The function of swear words in this case

is differentiating and integrating: they are to demonstrate the

distancing of the person from the official sphere and to show the

integration of a person into the УpeopleТs sphereФ (Уthe large

worldФ) and into his own subculture (not only student, but youth

subculture in general). Oppositionist approach is naturally

present here, though it is not consciously realized by the

cultureТs representatives. Unfortunately, for many young people

swear words are a mark of

freedom and absence of inhibitions in a person, of democratic

communication, that is why they remain prestigious among the

young.

The informational value of the studentsТ

epigraphy is exceptionally high. It is graffiti that show us the

whole range of musical and sports likings of the young (view the

photo), that tell us about their political views, esthetic tastes

and Ц what is most important Ц about the most Уsore issuesФ which

are not as a rule discussed with adults (first of all, sexual

life). It is graffiti that being an Уalternative to the official

discourseФ

11 convince us that the student is in a major degree

Homo ludens and it is not possible not to take this fact

into account in pedagogical activity.

The image of Уthe funny and the resourcefulФ

was born long before the appearance of the KVN game itself (

the Russian abbreviation for

A Club for the Funny and the Resourceful) and it is

remarkable that the game, stemming from the legendary students

Уjoking partiesФ and remaining a phenomenon of studentsТ

subculture, has overstepped the boundaries of the subculture and

has become an integral part of the common Soviet and post-Soviet

culture thanks to the television. Resourcefulness (ingenuity,

wit) is the opposite of Уtime-consumingФ and УworkaholicФ which

are, alas, indispensable for fundamental sciences and, in fact,†

the basically folklore (relayed through jokes and graffiti) image

of the truant student is simply a modification of Ivan the fool

who is, for some reason, inevitably lucky unlike his УpositiveФ

and hard-working brothers. The notorious УlazinessФ of† students,

a demonstrative unwillingness to study (to perform their basic

duty) is not, in a number of cases, the reflection of real

inclinations but just a convenient

mask that allows to hide for a certain period of time the

studentТs creativity and considerable mobilizing reserves.

The Уhumorous worldФ of students is really

all-encompassing: desanctification of both the Science and the

УTemple of ScienceФ and its priests has taken place long ago and

there is nothing to be done about it. One of the key reasons for

it may be the fact that Уacademic liberties give an independent

and critical view of lifeФ

12. Total ridicule of everything and everyone,

burlesque overturning of high values and ideals are salvation

from boredom and dreariness of every-day life, from

over-seriousness of its Majesty Уthe learning processФ. That is

why one of the answers to the question: УWhy do people write on

desks and walls?Ф was УkiddingФ. The word explains many things.

It is clear that the phenomenon is very ancient; what was

Diogenes doing if not kidding? Nevertheless, if we take

Уkidding as a factor of modern cultureФ and realize that

Уto be kidding means to express oneself in a creative way and to

demonstrate the freedom of thought and of action in an individual

and original mannerФ

13, then we have to admit that the young have an

existential need in such kind of Уcreative behaviorФ.

(M.M. Bakhtin) Despite the proclivity to topple over everything,

the student subculture keeps their Уfaith in the possibility of

communicationФ that was called Уphilosophic faithФ and viewed as

the only possible salvation for the humanity by K. Jaspers.

Through the roughness and Уholy simplicityФ of student epigraphy

it is easy to see

a breathing human feeling,

a natural self-expression of the personality warmed by

the limitless self-irony (which is a sign of moral

health), it is easy to hear an eternal cry of every intelligent

human being: I want to be understood!

1.†√уревич ѕ.—. —убкультура // ультурологи€. ’’ век.

Ёнциклопеди€,Ц —ѕб., 1998.Ц “.2 Ц —. 236.

2.†

See

,

for

example

: иселЄва†ё.ћ. ћаги€ и поверь€ в московском медучилище //

∆ива€ старина. Ц1995. Ц є1.Ц —. 23; јнекдоты наших читателей.

¬ып. 1-45. Ц ћ., 1996 Ц (Ѕиб

-

ка У—туденческого меридианаФ); ћадлевска€ ≈.Ћ. ”каз. cоч. Ц

C. 33-34; Ћис†“.¬., –азумова†».ј. —туденческий экзаменационный

фольклор // ∆ива€ старина.Ц 2000.Ц є4. Ц —. 31Ц33; ’арчишин†ќ.

Ќовочасний фольклор Ћьвова

: творенн€, функц≥онуванн€, специф≥ка репертуару

// ћатер≥али до украњнськоњ етнолог≥њ. «б. наук. праць. Ц ињв.,

2002. Ц ¬ип.. 2 (5). Ц —. 435 Ц437; Ѕорисенко ¬. ¬≥руванн€ у

повс€кденному житт≥ украњнц≥в на початку ’’≤ стол≥тт€ // ≈тн≥чна

≥стор≥€ народ≥в ™вропи: «б. наук. праць. Ц ињв

, 2003. Ц —. 4-10; оваль-‘учило ». „удесное в картине мира

современного студента в ”краине // „удесное и обыденное

:

/ —б. материалов науч. конф. Ц урск, 2003.Ц —.

9-15.

3.†

See

: Ўумов .Ё.

—туденческие традиции // —овременный городской фольклор. Ц

ћ., 2003.Ц —. 165 Ц 179; ћаталин†ћ.√. ‘ольклор военных училищ //

“ам же. Ц —. 180-185.

4.†

See

: Ѕажкова ≈.¬., Ћурье ћ.Ћ., Ўумов .Ё. √ородские граффити

// —овременный городской фольклор. Ц ћ., 2003. Ц —.

440

.

5.†Ќеклюдов —.ё. ‘ольклор современного города //

—овременный городской фольклор. Ц ћ., 2003. Ц —. 21.

6

.† Ѕажкова ≈.¬. и др. ”каз. соч. Ц —. 444.

7.†ѕлуцер-—арно ј. ћаги€ современного города //

http://www.

russ.

ru/

journal/

ist_

sovr/98-12-14/

pluts.

htm

8.†Ѕажкова ≈.¬. и др. ”каз. соч. Ц —. 445.

9. “ам же.

10.†Ўумов† .Ё. УЁротическиеФ студенческие граффити. Ќа

материалах студенческих аудиторий ѕермского университета // —екс

и эротика в русской традиционной культуре / —ост. ј.Ћ. “опорков.

Ц ћ., 1996. Ц —. 454.

11.†Ѕажкова ≈.¬. и др. ”каз. соч. Ц —. 4

38

.

12.† равченко ј.». ультурологи€: ”чебное пособие дл€

вузов. Ц ћ.

,

2000. Ц —. 335.

13.†¬черашн€€ ј. ѕрикол как фактор современной культуры //

ƒикое поле. ƒонецкий проект. »нтеллектуально-художественный

журнал.Ц ƒонецк, 2002. Ц ¬ып. 2. Ц —. 172-179.

ћихайло расиков

(’арк≥в)

†

”крањнська студентська субкультура у дзеркал≥

еп≥граф≥ки

†

” робот≥ досл≥джуютьс€ наст≥льн≥ та наст≥нн≥

написи ≥ малюнки харк≥вських та кињвських студент≥в, з≥бран≥

автором прот€гом 1990Ц2005†рр. ÷≥ граф≥т≥ (б≥льш≥сть з €ких Ї

ф≥ксац≥Їю фольклорних твор≥в) дають змогу скласти† у€вленн€ не

т≥льки про музичн≥, спортивн≥, пол≥тичн≥ та ≥нш≥ уподобанн€

студент≥в, а й взагал≥ зТ€сувати сутн≥сн≥ характеристики

студентськоњ субкультури. як св≥дчить еп≥граф≥ка, ними в першу

чергу Ї в≥дкрит≥сть, безупинне прагненн€ до всеб≥чноњ

комун≥кац≥њ, висока ц≥нн≥сть в≥льного самови€вленн€ особистост≥,

дом≥нуванн€ см≥хового та ≥грового (карнавального)

елемент≥в.

|